Certain amendments made to Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010 were made vide Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Act, 2020 and the same were given effect from 29.09.2020. The Government has proposed the said amendments after taking into the consideration the rampant misusage and abuse of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010 (for brevity ‘FCRA’).

The Government after noticing that allowing the transfer of foreign contribution by recipient to another transferee has created a huge layers of transactions, thereby found it difficult to trace and find whether the donations are being used for the reason that they were being received. Further, the current law allows utilisation of 50% of the amount received qua donation for meeting the administrative expenses. With the above two provisions in place, certain entities deployed strategies to divert the donations and expend the majority amount towards administrative expenses, leaving a miniscule amount to be spent for the ultimate purpose for which the donation was received. The amendment act proposed to prohibit the transfer of foreign contributions (donations) to another third party/transferee, thereby putting the complete onus of spending on the recipient. Further, the cap on the administrative expenses was brought down to 20% from the existing 50%. In addition to the above changes, the amendment act also proposed the persons who are willing to take registrations or prior permission for receipt of foreign contribution, to open an account with a designated bank unlike the current procedure of opening the bank account at the choice of applicant.

The above amendments were challenged on various grounds contending that the same are manifestly arbitrary, unreasonable and impinging upon the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 14, 19 and 21 of Constitution of India. On the other hand, the Union of India contended that the said changes are necessary in light of the experience gained and the misuse of the current framework.

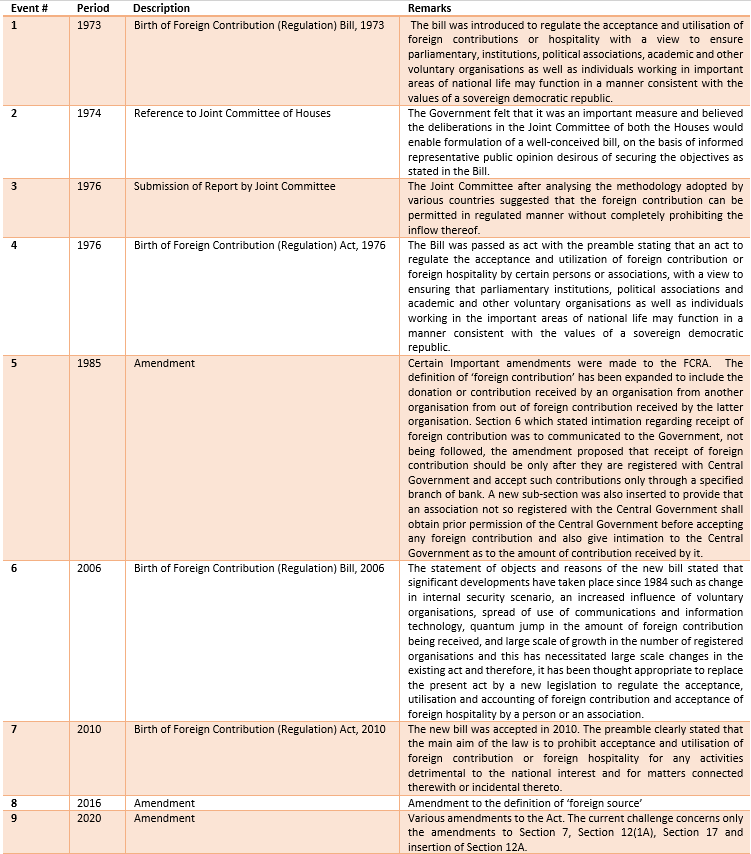

The Supreme Court after tracing the history of the legislation and the experiences which resulted in the misuse of the current framework has upheld the amendments and consequently rejected the petitions. In this article, we shall analyse the said judgment. Before going to the observations of Supreme Court, a brief timeline of the subject legislation is called for, which is as under:

Observations by Supreme Court:

The Supreme Court after hearing to the Petitioners and Union of India has held that it is well-established that rights guaranteed under Part III of Constitution and Article 19 in particular, are not absolute rights. The same are subjected to reasonable restrictions, as provided in Article 19 (2) and (6). The Court held that the Government is right when they contended that whenever the challenge is to the amended provisions, the scope of enquiry, inter alia, ought to be as to whether the same is consonance with the Principal Act, achieve the object and purpose of the Principal Act and are otherwise just, rational and reasonable. Further, there is no fundamental right vested in anyone to receive foreign contribution and that the purport of Principal Act and the impugned amendments are only to provide a regulatory framework and not one of complete prohibition.

The Court stated that Philosophically, foreign contribution (donation) is akin to the gratifying intoxicant replete with medicinal properties and may work like a nectar. However, it serves as a medicine so long as it is consumed (utilised) moderately and discreetly, for serving the larger scale of humanity. Otherwise, this artifice has the capability of inflicting pain, suffering and turmoil as being caused by the toxic substance (potent tool) – across the nation. The Court stated that, free and uncontrolled flow of foreign contribution has the potentials of impacting the sovereignty and integrity of nation, its public order and also working against the interests of the general public. It must be borne in mind that the legislation under consideration must be understood in the context of the underlying intent of insulating the democratic polity from the adverse influence of foreign contribution remitted by foreign sources.

The Court stated that many recipients had failed to adhere to and fulfil the statutory compliances – which resulted in cancellation of as many as 19,000 certificates of concerned persons/organisations during the stated period, including initiation of criminal investigation concerning outright misappropriation or misutilisation of foreign contribution. The Court held that it was increasingly reported that some of the NGOs were primarily involved in routing of foreign contributions accepted by them and not utilising the same itself for the purposes for which certificate of registration was issued and such transfer created several operational issues bordering on malpractices impacting the very intent of Principal Act. For, routing of foreign contributions entails in diverting it to another area of activity including misuse thereof. The Court noticed that there had been cases of successive transfers and creation of layered trail of money making it difficult to trace the flow and final utilisation. It was in this backdrop, to strengthen the compliance mechanism and enhancing transparency and accountability in matter of acceptance and utilisation of foreign contributions, the Parliament had to once again step in to restructure the dispensation, making it more meaningful and effective, so as to deal with the increasing impact of foreign contribution.

The Court held that it is open to a sovereign democratic nation to completely prohibit acceptance of foreign donation on the ground that it undermines the constitutional morality of nation, as it is indicative of the nation being incapable of looking after its own affairs and needs of its citizens. The third world countries may welcome foreign donation, but it is open to a nation, which is committed and enduring to be self-reliant and variously capable of shouldering its own needs, to opt for a policy of complete prohibition of inflow/acceptance of foreign contributions from foreign source and this was the first option noted by Parliament while considering the Bill concerning the 1976 Act. The Court stated that it is suffice to observe that considering the legislative history and the need for the Parliament to periodically intervene to arrest the increasing influence on the polity of the nation due to high volume of inflow of foreign contribution and large-scale improper utilisation and misappropriation thereof, as noticed by the authorities and keeping in mind the objective of the of the principle enactment being to uphold the values of sovereign democratic republic, the dispensation as altered to make it more strict compliance mechanism for ensuring that the foreign funds are accepted in the prescribed manner and utilised by the recipient itself and more so, for the purposes for which it was allowed to be received by that person, the amended provisions ought to pass the muster of reasonable restriction. The Court stated that such a change cannot be labelled as irrational much less manifestly, arbitrary, especially when it applies uniformly to a class of persons without any discrimination. The Court referred to the decisions in Rustom Cavasjee Cooper (1970) 1 SCC 248 and RK Garg (1981) 4 SCC 675, wherein it was held that it is not for Court to consider relative merits of the different political theories or economic policies including that an economic legislation may be troubled with crudities, inequities, uncertainties or possibility of abuse cannot be the basis for striking it down.

On Challenge to Amended Section 7:

The Petitioners have challenged amended Section 7, by stating that unamended provision though restricted the transfer of foreign contribution, yet it did not completely prohibit the same unlike the amended Section 7. The amended Section 7 postulates complete prohibition on the transfer of foreign contribution to other person – not even to a person having certificate of registration under the Act and make it mandatory to use the amounts only by itself and not through any person. The Petitioners stated that the change is also arbitrary and directly affects the implementation of the social upliftment schemes of the Petitioners through foreign contribution. The blanket ban on transfer of foreign contributions, thus affecting the collaborations in developing eco-systems, especially for smaller and less viable grassroot organisations that may not meet the criteria or be able to submit detailed proposals to get access to grants from foreign countries. The Petitioners contented that grassroot organisations, in some cases, may not have the track record or meet the eligibility criteria to obtain registration under the Act and are entirely dependent on the funding/transfer by foundations, such as Petitioners. The Petitioners contended that the intermediary organisations, which provide the necessary identification, monitoring and capacity building of the smaller non-profit organisations, which would be completely jeopardised because of the smaller non-profit organisations and for the reasons, the Petitioners challenged the amended provisions as violative of the rights guaranteed under Articles 19(1)(c) and 19(1)(a) of Constitution and also urged that the amendment suffer from vice of ambiguity and overbreadth or over-governance, thereby violating Article 14 as well. The Respondents countered on the argument that the Parliament in its wisdom has decided to introduce a stricter regime in the backdrop of experience gained from the implementation of unamended Section 7 and to eradicate the mischief which had unfolded.

The Court held that, as per scheme of 2010 Act, a certificate of registration is not granted for acting as an intermediary between the donor (foreign source) and the grassroot level organisation. The amended provisions, therefore, completely rules out such transfer of foreign contribution by the person who has received/accepted the same in the first place and that does not prevent the recipient from utilising the foreign contribution ‘itself’ for the purposes for which he has been granted a certificate of registration or obtained prior permission under the Act. The Court held that expression ‘transfer’ has not been defined under the Act and the meaning of such expression in the subject enactment would presuppose giving away of the foreign contribution in whole or in part to third person without retaining any control thereon, and such change of hands is obviously without offering any services in return, namely free of costs. The third person would then be free to deal with such transferred foreign contribution in the manner he chooses to do so, whilst adhering to the conditions specified in his certificate of registration or the conditions specified in the prior permission in his certificate of registration or the conditions specified in the prior permission, as the case may be. In this scenario, it had been possible that the transferor (who had accepted the foreign contribution) may have persuaded the foreign source to donate for one permitted purpose, but without consulting the donor (foreign source) could transfer the whole or part amount (foreign donation) to third person (transferee) for being utilised for altogether another purpose, which in a given case may not be acceptable to donor and thus paving way for misutilisation of foreign contribution and the possibility of abuse thereof. The Court stated that the rationale of Section 7 as amended, inter alia, is that the donor (foreign source) is made fully aware of the definite purposes already declared by the recipient and permitted by competent authority and corresponding obligation upon the recipient regarding utilisation of funds itself for stated purposes and none else. Indeed the expression ‘utilisation’ has also not been defined in the Act and by adopting the ordinary meaning, it must be understood in the context of the purpose for which a certificate of registration or prior permission has been granted by Central Government. If the foreign contribution is utilised for such definite purposes, including administrative expenses, outsources its certain activities to third person, whilst undertaking definite activities itself and had to pay therefore, it would be a case of utilisation. The transfer within the meaning of Section 7, therefore, would be a case of per se (simplicitor) transfer by recipient of foreign contribution to third party without requiring to engage in definite activities of cultural, economic, educational or social programme of the recipient of foreign contribution, for which the recipient had obtained a certificate of registration from the Central Government. The Court stated that on this interpretation, the challenge to ultra vires must fail.

The Court stated that on conjoint reading of Section 7 and Section 8 (which puts a cap on usage for administrative expenses qua foreign contribution received), the legislative intent of mandating utilisation of foreign contribution by recipient itself for the purposes for which it had been permitted gets reinforced. The Court also rejected the contention canvassed by Petitioners that in certain cases, the transferee would also have a certificate of registration and prohibiting the transfer to such persons also does not intend to serve any legitimate purpose by stating that legislative intent is to introduce strict dispensation qua the recipient of foreign contribution to utilise the same ‘itself’ for the purposes for which it has been permitted as per the certificate of registration or permission granted. The Court stated that absent such stringent provision, some of the recipient organisations were reportedly indulging in successive chain of transfers to other organisations, thereby creating a layered trail of money and utilisation of funds towards administrative costs of successive transfers upto fifty percent leaving very little funds for spending on the purposes for which it is permitted. Hence, the Court stated that providing complete restriction on transfer simplicitor, was the just option to fix accountability of the recipient organisation and maximise utilisation for the permitted purposes. The Court stated that revoking the provision to transfer from Section 7 cannot be basis to challenge the validity of the amended provision since it is open to the Parliament to change the benchmark of restriction from higher to lower standard or vice versa on the basis of exigencies and experience.

On Challenge to Amended Section 12(1A) and Section 17(1):

Section 12(1A) has been inserted by Amendment Act, which envisages that every person who makes an application under Section 12(1) is obliged to open FCRA account in the manner specified in Section 17. The sub-section (1) of Section 17 was amended to mandate that every person who had been granted certificate or prior permission under Section 12 shall receive foreign contribution only in account designated as FCRA account in the specified bank. The unamended Section 12 and Section 17 did not impose such restriction. The Court stated that the above amendment introduced in light of the abuse under the unamended provisions cannot be struck down. The Court held that there is a force in the argument of Respondents that Section 17 came to be amended aftermath realisation of clear and discernible lacunae had cropped in due to the presence of FCRA accounts of scores of registered organisations, in different scheduled banks across the country. The challenge became more pronounced due to doubling of contributions inflow in the last decade which had impacted the efficiency of monitoring and achieving the object of Principal Act. The Court held that the fact that earlier FCRA account could be opened in any scheduled bank, cannot preclude the Parliament from legislating a law which requires inflow of foreign contribution in some other manner specified by law. Introducing change for betterment of governance is prerogative and wisdom of Parliament. The FCRA account operators cannot claim right of continuity of a deficient and flawed framework. The Court stated that ordinarily, convenience of business and persons engaged in doing business must be uppermost in the mind of Parliament to effectuate the goal of ease of doing business. However, the strict regime had become essential because of past experience of abuse and misutilisation of the ‘foreign contribution’. Hence, there has been legitimate goal for amending the subject provisions of acceptance of funds through one channel and concededly, despite the requirement of opening FCRA account in the designated bank, it is open to the organisation to utilise the amount so received in FCRA account through multiple accounts in the scheduled branches and concluded that it is a balance approach by Respondents. The Court held that in the context of law made by Parliament in the interests of sovereignty and integrity of country and security of the State, public order, as also in the interests of general public, such a provision cannot be lightly viewed much less on the specious plea of manifestly arbitrary.